Before the General Election, Zac looked at party manifestos and what young people would find interesting in each. We asked Zac to take another look at policy, now that the election result is settled.

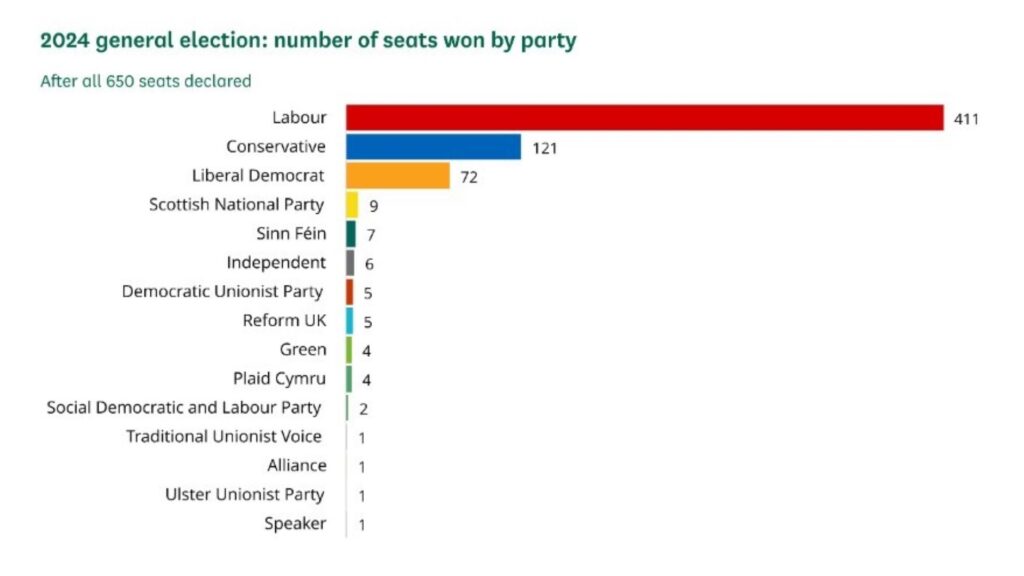

At the General Election earlier this month, the Labour Party achieved a historic feat and gained 209 seats, bringing their total number of seats to 411, well past the 326 seats needed to form a government.

Britain once again has a Labour government, for the first time since 2010.

But what does this result mean for young people?

In their election manifesto, Labour aimed several policies at young people. Among other commitments, they promised to:

- Ban zero-hour contracts, along with the practice of fire and rehire

- Increase minimum wage to a “living wage” and remove the age banding for minimum wage, so that all adults were paid the same irrespective of age

- Lower the voting age to 16

- Reform employment support, bringing back Job Centre Plus and the National Careers Service.

Labour have stated the ‘genuine’ living wage they are proposing will take the cost-of-living crisis into account, but have yet to release specific details concerning this.

For reference, minimum wage at the time of writing in July 2024 is £11.44 for those aged 21 and over, £8.60 for those 18 to 20, and £6.40 for those under 18.

Labour intends to scrap this age banding system in favour of a flat minimum wage for all workers. These pledges are part of what Labour calls its ‘new deal for working people’ and the party has stated it will implement these via legislation within 100 days of coming into government.

But what else could they do?

While these changes would surely be welcomed by young people, there is a feeling that Labour could do more and should consider other policies such as:

- Introducing rent caps

- Reform of tuition fee system: abolition, a reduction or the removal of interest rates on repayments

- Re-join the Erasmus Plus programme.

Though the above measures may prove difficult to implement, both politically and economically, it should not be underestimated just how much they would help younger people.

A recent report from the BBC shows that almost 1.8million people owe £50,000 or more in student debt, with some students unable to even begin paying the debt off and instead only paying back the mounting interest.

Those graduating with such debt are then tasked with finding somewhere to live in a system with very few affordable homes, and a rental market in which private landlords hold most of the power.

Though Labour have set out plans to build new homes, they have pledged little change to the rental market, and it is in the rental market that young people typically find themselves looking for accommodation as they have generally not yet saved enough money for a property deposit.

Labour should also consider returning to the Erasmus Plus programme as an associated country, allowing young people to teach, volunteer, and study abroad, broadening their horizons and future employability prospects.

By implementing some or all of the above suggestions, Labour could begin to foster and nurture a symbiotic relationship with younger people, especially if they reduce the voting age to 16.

An article from The Guardian states that doing so imminently would add roughly 1.5 million people to the electorate. This does not include those who are currently too young to vote now (those already 16 and 17 for example) but who will be eligible at the next election either.

If Labour can capitalize on this term in government and introduce any of these suggested policies, they would surely, sharply increase their support with young people, placing them in a very strong position for re-election when the time arises.

July 10, 2024