Dr Andrew McInnes is a specialist in romantic-period literature. He has recently been awarded funding from the arts and humanities research council to be an early career leadership fellow for his research project the romantic ridiculous, exploring how ridiculousness can help us to develop new perspectives on the romantic period of 1750-1850. So, let’s hear from Andrew.

What is the Romantic Ridiculous?

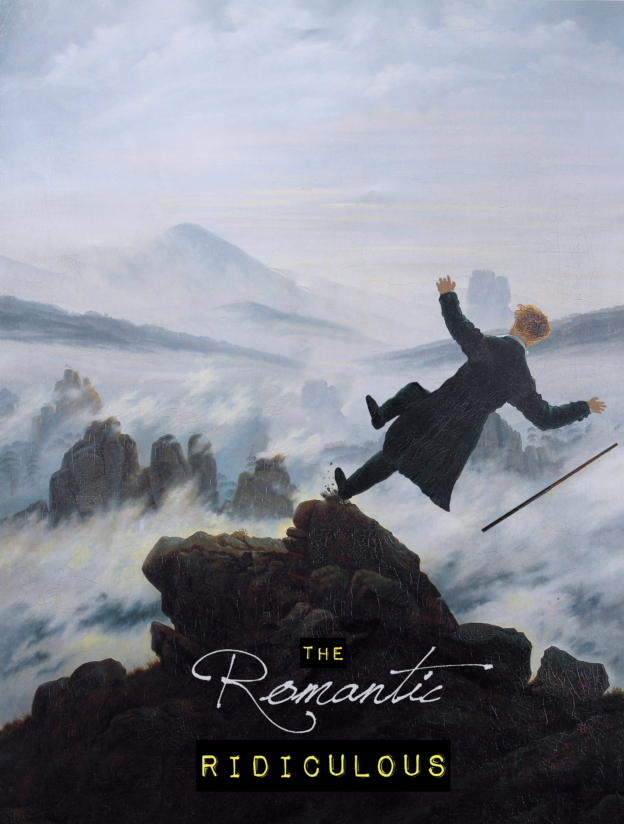

The Romantic Ridiculous project aims to take Romantic studies from the sublime to the ridiculous. A powerful image from the period imagines a lone genius on top of a mountain, or in a field of daffodils, communing with nature in a way which celebrates the powers of creativity and imagination. My project questions the reality of that image by looking at collaboration and conversation in the period, bringing groups of people together in shared laughter. It is a two-year project which will result in academic articles and books, but also stresses the importance of collaboration and conversation in universities today.

So, I’m hosting a series of what I’ve called ‘Table Talks’, inspired by a popular genre from the Romantic period recording the conversations of famous writers, which brings academics and others together to discuss our work in progress. The project will culminate in a travelling exhibition co-produced with groups of local A Level students called Ridiculous Romantics, which will be displayed around the Lake District in collaboration with The Wordsworth Trust and Windermere Jetty: Museum of Boats, Steam, and Stories.

What romantic literature first fascinated you?

I actually avoided Romanticism when I was an undergraduate – imagining it was all poetry about flowers and mountain. I first got interested in Romantic period literature when I was working on my Masters thesis on Mary Wollstonecraft’s Letters from Sweden. Wollstonecraft was a pioneering feminist, philosopher, and novelist. Her Scandinavian travelogue innovatively combines autobiography, aesthetics, as well as travel writing. From there, I became interested in women’s writing at the end of the eighteenth and beginning of the nineteenth century, including novels by famous writers like Jane Austen and Mary Shelley, as well as less well known authors like Mary Hays and Charlotte Dacre, as well as Gothic fiction and children’s literature.

What literature inspired your research?

The Romantic Ridiculous is inspired by an anecdote from the poet Samuel Taylor Coleridge writing about his experience of falling down a mountain, which led to him ‘laughing at himself like a madman’. I wanted to pick a canonical Romantic poet and think about him in relation to the ridiculous instead of the sublime. As I worked on the project, I discovered that Coleridge himself thought about the ridiculous as the root of laughter and humour, and at times found himself ridiculous, too. He was inspired by a German philosopher and novelist called Jean Paul Richter who theorised the ridiculous as a counter-sublime based on an initial failure of understanding which forges a new perspective on life, bringing people together in shared laughter.

Why were you drawn to ‘ridiculousness’?

When I was first applying for jobs, I wanted to write on my CV that I had a ‘keen sense of the ridiculous’, inspired by Jane Austen’s most popular heroine, Lizzie Bennet from Pride and Prejudice. I’m interested in the funny side of literary studies and the ridiculous gives me a philosophical underpinning for my research, providing me with a way of interpreting and analysing Romantic period poetry, fiction, and philosophy, as well as thinking about Romantic legacies up to the twenty-first century.

What romantic literature would you recommend to your students?

Mary Wollstonecraft’s writing sounds fresh and urgent still today, demanding equal rights – and responsibilities – for women. Jane Austen is also fascinating, a funny writer who also has serious points to make about inequalities and injustice. In terms of off-the-beaten-track suggestions, I’m currently reading E T A Hoffman’s novel The Life and Opinions of Tomcat Murr, which, as the title suggests, is the autobiography of a cat who aims to become a Professor of Aesthetics.

What can students learn about romantic literature on their degree?

Students taking our romanticism module will read poetry about daffodils and mountains, which I’ve learned to love and admire, as well as less well-known poems on the consequences of the French Revolution and a fantastic poem which imagines living in a post-apocalyptic Britain. We also read Jane Austen’s Sense and Sensibility and Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein, as well as a play called De Monfort, a tragedy about hatred, written by a forgotten playwright, Joanna Baillie, once considered ‘Our Modern Shakespeare’. Students can also take author-focused modules on Jane Austen which also looks at adaptations like the BBC Pride and Prejudice and the film Clueless, the best adaptation of Emma ever.

Our all-year module on Children’s Literature thinks about the construct of the romantic child and its continuing influence today, looking at works from Lewis Carroll to Jacqueline Wilson, as well as less well known writers like Sarah Fielding, Julia Golding, and Lissa Evans.

June 5, 2022